Submitted by BRENCIS CYRUS -... on

Submitted by BRENCIS CYRUS -... on

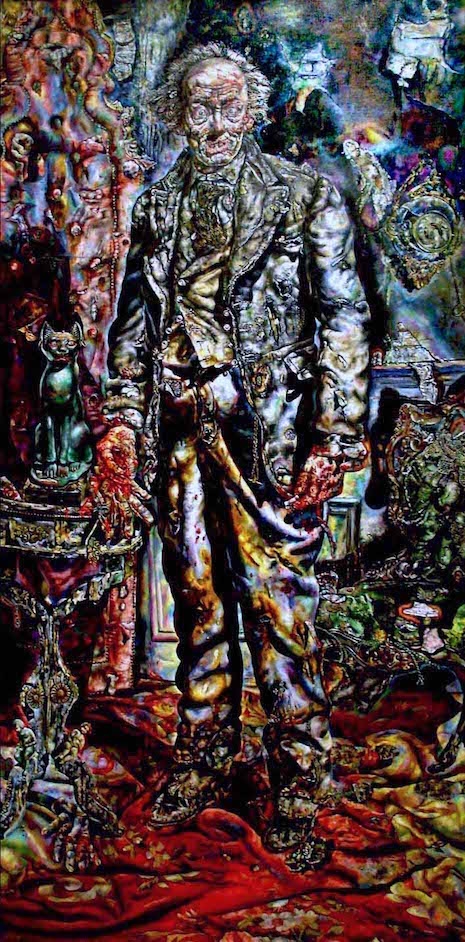

Staging of Dorian Gray discovering his portrait in a scene from the Arte documentary “Dorian Gray or: The Portrait of Oscar Wilde”.

Photo: Henrique Medina/Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc./Thomas Fage/Hauteville Production/Arte/dpa Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc./Thomas Fage/Hauteville Production/Arte

https://www.mz.de/kultur/tv-und-streaming/dorian-gray-oder-das-bildnis-des-oscar-wilde-1717873

The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde tells the story of a distinguished young man, Gray, whose portrait is painted by the artist Basil Hallward. On seeing the finished picture, Gray is overwhelmed by its (or rather his own) beauty and makes a pact with the Devil that he shall stay forever young with the painting grow old in his place. In modern parlance, consider it Faust for the selfie generation. Gray then abandons himself to every sin and imaginable depravity—the usual debauches of sex, drugs, and murder, etc.—in order to “cure the soul by means of the senses, and the senses by means of the soul.” As to be expected, this has catastrophic results for Gray and those unfortunate enough to be around him.

Wilde disingenuously claimed he wrote The Picture of Dorian Gray “in a few days” as the result of “a wager.” In fact, he had long considered writing such a Faustian tale and began work on it in the summer of 1889. The story went through various drafts before it was submitted for publication in Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine. Even then, Wilde contacted his publisher offering to lengthen the story (from thirteen to eventually twenty chapters) so it could be published as a novel which he believed would cause “a sensation.”

Dorian Gray by Alvin Albright (1943) - WikiCommons

Who was the inspiration for Dorian Gray?

John Gray (1866-1934), poet and priest - Wikipedia public domain

John Gray was the eldest of nine children born into a working-class family in Bethnal Green, London. His father was a wheelwright and carpenter. At fourteen, Gray was apprenticed as a metal worker at the Royal Arsenal involved in the production of munitions. However, he held secret ambitions to better himself and become a poet. He enrolled in night classes where he studied art, music, and languages. He then joined the civil service in 1882 and went onto study at the University of London before joining the Foreign Office as a librarian.

Gray started writing poetry and gravitated towards London’s bohemian art scene where he became friends with the artist Aubrey Beardsley, the poet Edward Dowson, and Oscar Wilde. Gray was an incredibly beautiful man. It has been claimed that even in his mid-twenties he had the sensuous beauty of a fifteen-year-old.

Gray first met Wilde in the summer of 1889 at a party in a Soho restaurant. Wilde was immediately besotted by Gray’s beauty. For his part, as noted by George Bernard Shaw, Gray was “the most abject of Wilde’s disciples.”

Whether Gray was the sole influence in the creation of “Dorian Gray” is a moot point. However, the conjunction of their first meeting in the summer of 1889 when Wilde started work on Dorian Gray around the same time does suggest some form of artistic cross-pollination. Moreover, Gray signed his letters to Wilde under the alias “Dorian.” Gray also later recalled receiving a letter from the playwright which stated:

The world is changed because you are made of ivory and gold. The curves of your lips rewrite history. *

Gray later loathed his association with the book and eventually denounced his relationship with Wilde and was ordained as a priest.

Six Reasons to read it:

The story is unlike anything else

Well, almost anything else. It certainly has echoes of the Greek mythical figure Narcissus (who fell in love with his own reflection), but The Picture of Dorian Gray is very much its own beast. It tells the story of a young, attractive socialite in nineteenth century London who is painted in a portrait. He semi-seriously prays for the painting, and not himself, to bear the burden of age and sin. As the years advance and his soul blackens, it becomes apparent that his supernatural wish has been granted. I remember watching the 2009 cinematic adaptation starring Ben Barnes as the titular character and Colin Firth as Lord Henry Wotton; the man responsible (or is he?) for leading Dorian astray. It probably wasn’t the ideal introduction to this story; the film is fairly flimsy and irons out many of the novel’s creases. Nonetheless, I vividly remember being captivated by the bare bones of the story, and how fantastically weird it was. Don’t bother with that movie (although I am told that the 1945 version is actually rather good). Instead, throw yourself into Wilde’s mesmerising original.

5. It’s short

OK, so perhaps this isn’t actually a reason to read this novel, but it certainly means there are no excuses not to (my edition is just shy of 150 pages). What is so incredible about Wilde’s writing style is its brevity. The author has a deftness of touch which means that however morbid or disturbing the subject matter might be getting, the reader can rest assured that he will not wallow in the macabre for page upon insufferable page. Instead, he manages to create the perfect balance of light and shade, his prose nimbly trotting from scene to scene.

4. It will lead to endless dinner-table discussion

In my mind, truly great art engages both the heart and the brain, and The Picture of Dorian Gray certainly fulfills this dual requirement. Whilst packing an emotional punch, the novel also invites one to question what the deceptively simple story actually means. Is Dorian’s vanity driven by his self-obsession or his fear of decrepitude? Are they actually the same thing? Wilde leaves enough unsaid to make room for the reader’s own unique stance. In my mind, the story is an allegory for the intrinsically human desire to project an idealistic ‘version’ of ourselves onto our surroundings. Despite all of our shortcomings and unsightly character traits, we strive – day in, day out – to mask these with layers of falsity. We are an innately deceitful species, desperately hiding our own decrepit ‘portraits’ from our friends, family and colleagues and instead upholding the pretence of the blemish-free Dorian. Well that’s my reading of the text, likely to differ enormously from yours. But that, of course, is the joy of this text; it doesn’t attempt to drive home a moral message, yet gently prompts discussion and debate.

3. Oscar Wilde is a wordsmith

It almost goes without saying that Wilde’s writing style is stunning. Beautifully poised, subtle and rich in meaning, it frequently contains images that have that rare ability to immerse one fully in the sights, sounds and smells of the world being described. Take, for example, the novel’s opening lines:

The studio was filled with the rich odour of roses, and when the light summer wind stirred amidst the trees of the garden, there came through the open door the heavy scent of the lilac, or the more delicate perfume of the pink-flowering thorn.

The reader’s introduction to the protagonist himself highlights Wilde’s masterful ability to encapsulate in just a few words the very essence of a character:

Lord Henry looked at him. Yes, he was certainly wonderfully handsome, with his finely curved scarlet lips, his frank blue eyes, his crisp gold hair. There was something in his face that made one trust him at once. All the candour of youth was there, as well as all youth’s passionate purity. One felt that he had kept himself unspotted from the world.

Instantly, we feel we know this character – actually know him – rather than him being just a name and an empty description. The author also succeeds in capturing in words that most elusive of places; the world of dreams:

There are few of us who have not sometimes wakened before dawn, either after one of those dreamless nights that make us almost enamoured of death, or one of those nights of horror and misshapen joy, when through the chambers of the brain sweep phantoms more terrible than reality itself, and instinct with that vivid life that lurks in all grotesques, and that lends to Gothic art its enduring vitality, this art being, one might fancy, especially the art of those whose minds have been troubled with the malady of reverie. Gradually white fingers creep through the curtains, and they appear to tremble. In black fantastic shapes, dumb shadows crawl into the corners of the room and crouch there.

It is a testament to Wilde’s supreme skill that his descriptions never grow stale. He is able to select the right words at the right time to evoke each and every face, room, street, ornament or sensation.

2. The preface is a fascinating read in itself

A slightly outlandish entry in this list, I admit, but a significant one nonetheless. Before I read The Picture of Dorian Gray, I don’t recall ever finding the preface to a book particularly memorable. In typical Wilde style, the preface to this novel is actually more of a mini-essay on the nature of art. It concludes with these powerful, short sentences:

All art is at once surface and symbol. Those who go beneath the surface do so at their peril. Those who read the symbol do so at their peril. It is the spectator, and not life, that art really mirrors. Diversity of opinion about a work of art shows that the work is new, complex, and vital. When critics disagree, the artist is in accord with himself. We can forgive a man for making a useful thing as long as he does not admire it. The only excuse for making a useless thing is that one admires it intensely. All art is quite useless.

In the vast majority of cases a mere literary convention, here the preface feels urgent, important and directly bound to the main work itself. Because, of course, the thrust of the story is instigated by a work of art; a work of art that ceases to be ‘surface and symbol’. Instead, Dorian himself takes on the superficiality and, as Wilde suggests, uselessness of a painting, becoming his own artwork to be ‘admire[d] […] intensely’. Of course, The Picture of Dorian Gray is, in itself, a work of art, making this preface take on a pointed significance. It prefigures exactly what I have been doing throughout this article; ‘read[ing] the symbol’ ingrained in the text. Thus the assertion ‘It is the spectator, and not life, that art really mirrors’ is exactly right; try as we might to uncover the innate meaning of any piece of art, we are inevitably just channeling our own opinions, beliefs and understandings.

1. It feels eerily relevant

I don’t want to over-labour the whole ‘this novel is just as relevant today as it was in 1890’ point, but there are undoubtedly some facets of modern society which are closely tied to themes in the book. The cult of the image is something which seems to have emerged as a deciding factor in the post-World War II, primarily Western world. Today, glamour magazines and adverts bombard us with Dorian-esque, unrealistic, skin-deep imagery every minute of every day. As I mentioned before, I see the novel as acutely picking up on one seemingly essential strand of human nature; the lust for our true character to be given a near-perfect outward-facing mask. This can be seen manifesting itself in everything from celebrity super-injunctions to choosing how you are represented on your Facebook profile. Read the novel yourself and I can guarantee you’ll unearth some parallels of your own. **

** https://the-artifice.com/read-the-picture-of-dorian-gray/

- 1448 reads